History of Bridgeview

Early Settlers

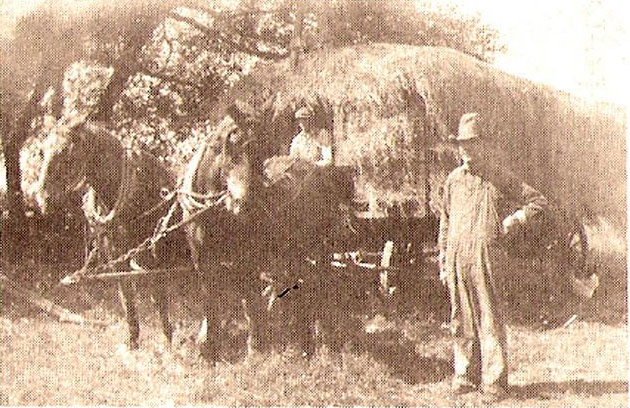

Indians and the first settlers are generally though to have opened clearings in the forests for the cultivation of corn and other grains. But this apparently was not true of the area at the southern end of Lake Michigan, where prairies were mixed with the forests. Most of the area from the mouth of the Chicago River at the lake front to where Bridgeview is now located (the old bed of lake Chicago) consisted of marshes, wet prairies and dry prairies, which provided good natural pasture and hay for grazing animals. Hay was one of the main products of the early farmers in the Bridgeview area. It was raised not only for their own use, but for Chicago’s large horse feed market. The chief farming crops were corn, wheat, oats and potatoes.

One of the earliest homes to be built, in what is now known as Bridgeview, was erected in the 1830’s at about the time the Indians were leaving the area. The home was located on the east side of the Archer Trail, just north of its intersection with Roberts Road. It was two-stories high, approximately 24 feet square of frame construction. It consisted of wood siding with bricks filling the spaces between the studs, certainly ample enough to stop both arrows and bullets! It had a cellar with two foot thick walls of stone. On the top of the building there was a lookout tower, which commanded an excellent view of each direction of the trail. The tower served as a high point from which to observe approaching storms, travelers or possibly Indians.

The house and land were rented in 1920 to the Buralli family, who had farmed at 7300 Archer Road for twenty years previously. The Burallis truck farmed at their new location until 1941, when they gave up farming. The building was torn down in 1948.

On the west side of Roberts Road at 76th Street, an early farmer named Egner lived in a house originally built by a farmer Struck in the 1840’s. A second house with a barn was built on the east side of Roberts Road in the 1860’s.

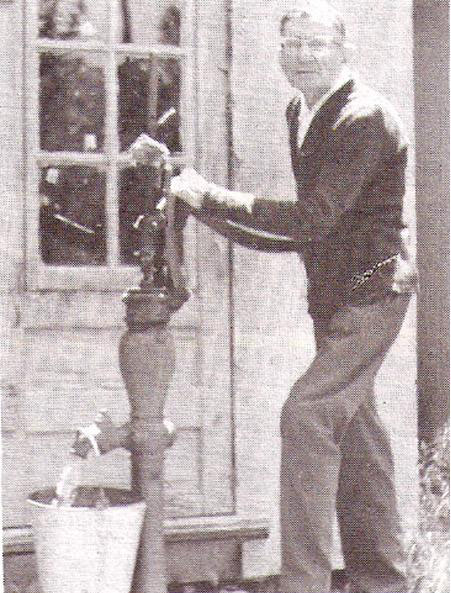

The house on the east side of Roberts Road was moved to the west side in the 1890’s. The Kopping well, located on the east side of the road, had to be dug to only ten feet because the clear cool water was spring fed. It was never known to go dry, even during the dry years of 1934 and 1936.

A number of people including the elder Fred Kopping contracted yellow fever in the 1890’s. The disease was thought to have been caused by stagnant floodwaters that had entered the low areas of Justice. But the problem was resolved when the Ship and Sanitary Canal was opened in 1900, permitting the water to run off.

In 1904, after a good summer’s crop of hay had been harvested into six huge stacks plus one wire tied stack from the previous year on the east side of Roberts Road, a thunderstorm blanketed the otherwise serene farmland. With a loud crack, a lightning bolt (probably attracted by the wire) struck the end haystack setting it afire. Within moments the great haystack formed a raging bonfire, fed with oxygen from its own updraft. The searing heat of the first stack soon ignited the second, which in turn moved to the next until all seven mounds went up in flames and smoke. The tons of hay, a whole season’s crop, were wiped out by one unfortunate quirk of nature. The barn was saved with the help of neighbors who threw canvas over the building and kept it wet by means of a bucket brigade.

The Koppings had seven sons and four daughters born to them between 1882 and 1898. Two of the boys later became motormen for a Chicago streetcar company. The elder Kopping died in 1929. Some of the children stayed on the farm until 1942. A son, Charles, born in 1896 told one of our historians that he recalled one particular day in 1916. Charles was driving an empty hay wagon south on Roberts Road at about 72nd, when he heard a steam locomotive whistle and saw the afternoon sun reflect off a Wabash railroad train traveling southwest towards 111th Street. A four-mile unobstructed view over the flat open prairies!

Just to the south of the Kopping farm on the west side of Roberts Road was a farm occupied from about 1890 until 1903 by the Balimore and Roszik Brewery Company. Horses used for pulling beer wagons in Chicago were sent here if they became sick, injured or just too old to work.

Herman Schmidt. Sr.

In 1903, two German immigrants, Herman Schmidt, Sr. and his wife, leased the property. They started their own milk dairy in 1910, in addition to raising the usual farm crops. One of the first telephones in the area was installed that year for use by the dairy. One day in 1917 at about noon, lightning struck the barn burning it along with three cows and two horses. Due to the additional cost of equipment required for pasteurization, the Schmidts sold their dairy business to the Brown Dairy of Summit in 1918. The Schmidts, who had five boys and two girls, moved from the farm in 1937 after auctioning off their equipment and some of the larger buildings they owned. The remaining buildings disappeared, piece by piece, probably for use as firewood during the depression years.

Sometime near 1860, German born Charles Hosman and his wife came to America on a sailing vessel. From the east coast they made their way to just beyond the burgeoning city of Chicago. They bought 79 acres of land and began farming. The home they built, although remodeled considerably, still stands on the northeast corner of Roberts Road and 89th Street. The time of the elder Hosman’s death is unknown, but two of his sons, Henry and Fred, remained on the farm after their brother, Christ, married and left the family farm in 1898. Cream produced from the Hosman’s herd of cows was used to make butter, which they sold to a store (owned by the Raddatz family) in Summit. Henry and Fred sold their hay in Chicago. The Hosmans often took wheat and rye grain to a waterwheel gristmill where it was ground into flour for their own use. During prohibition they made rye whiskey, which was served as a treat to the local farmers when they got together at threshing time.

Henry Hosman was the first person in the area to purchase an automobile, a 1911 Ford touring car, in which he made a weekly journey up Roberts Road to shop and trade in Summit. After he died in 1936, the car was kep in a shed on the property. The back end was kept jacked up with a rear wheel belted to a buzz saw for cutting firewood. Fred Hosman died in 1946.

Christ Hosman married in 1898 and built a home at the southeast corner of Roberts Road and 71st Street. He started farming on 160 acres of leased land on both sides of Roberts Road from 71st to 75th Streets. Farming on the west side was much better than the east, which had poor drainage. Late in the summer of 1914, just when four huge haystacks on the west side of Roberts Road were ready for baling, a fire was started at the nearby cemetery to burn accumulated tree and bush clippings. With a brisk southwest wind blowing, sparks and burning embers were carried to the Hosman haystacks. With the help of farmer August Kluck, who was passing by, and the Koppings, one of the haystacks was saved but the other three were burned to the ground. Most of the summer’s hay harvest was lost in minutes.

The Christ Hosman farm produced its own electricity by means of a “Delco” system consisting of sixteen storage batteries charged by a gasoline generator. Water was drawn from a 165 foot well, quite a contrast to the ten foot depth of the Kopping springfed well.

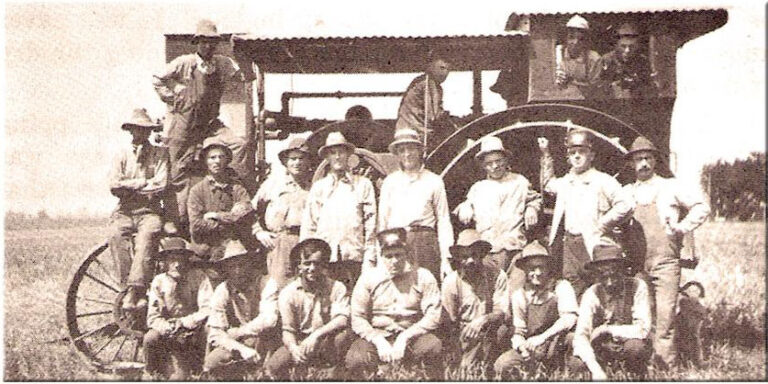

The farmers’ main social events were at threshing time, when they helped each other as the threshing machine made its rounds, and when there was a wedding. Weddings were usually arranged to take place in May or June, before the haying season, so that an empty barn would be available for the festive event.

In 1922, Resurrection Cemetery purchased the west land that Christ Hosman was farming. It was at that time, when Christ bought three acres of property on the east side of Roberts Road, which included a house, barn and out buildings. Hosman then gave up farming, auctioned his equipment and went to work for a greenhouse. He died in 1948. His son, Sidney, owned and operated his own greenhouse at the 71st Street and Roberts Road location until he sold it to the present owners of Bella Flowers.

August Kluck

The Charles J. Kluck family came from Indiana to the Chicago area in 1881. A son, August, born in 1877, worked for a time at the Columbian Exposition of 1893. He married in 1903 and lesed 60 acres of farmland located between 75th and 79th Streets, the railroad and 7800 west. As a wedding gift his parents gave him two horses.

One evening during their first summer, lightning struck the barn during a quiet rain, setting it afire. August Kluck ran to the barn where he found his two gift horses had been struck dead by lightning. As he carried out a colt, he was followed by a mare with its mane on fire. And although the mare was permanently blinded by the flames, Kluck kept the horse and was able to work it for several years.

August Kluck also farmed 160 acres of land just north of 71st Street between Roberts Road and Harlem Avenue. The portion east of the railroad was used for growing hay, the remainder for corn, wheat, oats and potatoes. In winter Kluck and his team of horses would sometimes hire out with other farmers to cut ice blocks from Lake Michigan. The ice was stored for summer use in buildings constructed for this purpose. Kluck also worked during winters with his horse teams delivering building materials for C.C. Waggoner of Summit.

In 1929, the Klucks moved to Chicago. They stayed there for one year and were about to return to their farm when they received a Sunday morning telephone call from neighbor farmer Herman Schmidt. Schmidt informed Kluck that his farm home and attached summer kitchen had burned to a complete loss the night before. Undaunted, Kluck built a new home soon afterwards.

Kluck often put up a hundred tons of hay in one year. In 1933, thirty years after his first barn burned, he was baling hay in his barn when a spark from the gasoline driven baler ignited the hay. He was able to save three horses and a harness, but the barn was completely burned.

The Klucks had two daughters and a son. Their daughter, Harriet, married Charles Thier in 1938 and built a small home on 79th Street. Mrs. Kluck died in 1952. The following year the farm home was moved from its location at 7800 south and east of 78th Avenue to its present location at 78th Avenue and 79th Street.

August Kluck actively farmed until his death in 1963. Charles Thier died in 1971, but his wife Harriet continued to live in the original farm home. The third and last Kluck barn was burned down by the Bridgeview Fire Department in 1964.

Herbert Hartman

Herbert Hartman was born on a farm in New Salem, North Dakota on December 8, 1903. The family moved to Chicago in 1915 where they lived until 1921. That’s when they rented 60 acres of farmland between 83rd and 79th Streets, Roberts Road and 78th Avenue. The Hartman’s raised hay, corn, oats, wheat and had cows and horses on this land, previously rented by a farmer named Klawitter. In 1927, the elder Hartman purchased 10 acres at the northeast corner of 83rd Street and Roberts Road. It was recorded in 1972 that his son Herbert was still residing there with his wife.

Herbert recalled the cockfights held at the Kelso farm on the west side of Roberts Road at about 85th Street. The illegal sport was halted periodically sue to raids by the local sheriff. The Kelso farm later became the Katt farm, which was then purchased by the Bartlett Real Estate Co. A farmhouse on the property was converted into a tavern. Hartmann recalled that the tavern became a speakeasy during prohibition. Sometimes he was summoned late at night by the proprietor to use his team of horses to pull a customer’s car out of muddy Roberts Road and haul it to 95th St.

In the late 1930’s, Herbert Hartman sometimes had a teenaged boy help him cut hay on the Belke property located on 79th Street west of Harlem Avenue. The youth was Louis Defazio, whose father had a small farm at the southeast corner of 75th Street and Selma Avenue. The elder Defazio started farming here in 1921. As an adult, Louis stayed in Bridgeview and became a homebuilder.

Hartman kept horses and cows on his land until 1965, when he retired. Other small farm buildings, besides the house were still standing in 1972.

At 7300 W. 79th Street, one block west of Harlem Avenue and 150 feet north, (now on Park District property) stands a rather stately looking two-story frame house. It had been the home of August Belke and his wife, who bought the property in about 1905. A German-born farmer had lived there previously. The Belkes farmed in three other locations in this general area before settling on 79th Street.

A barn on the property burned in 1910 and the original home burned in 1911, after which the present house was constructed. Belke erected the house, which he purchased from Sears Roebuck & Co. as a unit. Belke was the second person in this area to own an automobile, a 1912 Ford. He also owned one of the area’s few threshing machines, which he made available for use by nearby farmers. The machine was pulled by a gasoline fueled tractor, which served as the power drive for the unit. Belke also owned a hay baling machine and a corn shredder. He worked for the International Harvester Company.

Local Farmers

A son, William, was the last of five sons and two daughters to reside in the Belke home. William was employed by the Lyons Township road department and paved roads of the early Bridgeview community using cinders from the Argo Corn Products Company. These cinders form the base of some of our present village streets.

The “owner rights” of the Belkes were invoked one time when the railroad, which ran past the front of the home along 79th Street, decided to block off the only access to the property. The conflict went to court, where it was ruled that the railroad had to allow a permanent access to the home over their right of way.

William Belke died in 1952. His wife Minnie was 72 yrs old when she died in 1967. The house is now owned by the Bridgeview Park District and is considered a Bridgeview landmark. The original 1906 concrete storage shed still stands behind the old Belke house today. (pictured below)